This article started with a personal task of formulating some kind of strategy to overcome the ‘common’ academic crises that crop up occasionally and detract from all of the fun and exciting aspects of my work. I started by thinking about the most common crises that academics face, including periods of extreme stress or anxiety (either self imposed or externally driven), being overwhelmed thinking about, and strategising for, the future, applying for jobs and grants, getting rejected from jobs and grants, as well as experiments/manuscripts/collaborations not going as planned (in addition to all the challenges in people’s personal lives). I thought that my resulting ‘academic crisis management plan’ might also be useful for others, despite being personal and not fully comprehensive. I think with a bit of imagination, many of the ideas here could be of use for people at any point in the academic pipeline, from students to PIs, after all we all categorise what constitutes a crisis very differently.

Academia is a difficult, competitive, career to make work. As a result, I think that both personal and professional crises or mini-crises are quite common (if you think this is a bit melodramatic then just replace the word crisis every time you read it with stressor). Perhaps I’ll write a post about whether I think the competition and resulting crises are unique to academia, or intrinsically a good or a bad thing another time, but I think this sentiment is pretty inarguable. I also think that pretending this isn’t the case, that pursuing an academic career isn’t difficult or doesn’t involve dealing with a sometimes flawed system, regardless of how much we wish it weren’t, is largely unhelpful and doesn’t help us address the different challenges we face both personally, and as a community. As a postdoc (and twitter user) I’ve become very aware of the breadth of common obstacles that everybody has to navigate from time to time in pursuit of an academic career. I’m also aware that in addition to these ‘common’ obstacles that impact everyone, there are additional obstacles that have a disproportionate, and frankly unfair, impact on specific fractions of our academic community in a manner of different ways. In this regard I count myself very privileged, having to predominantly navigate only what I deem as the most ‘common’ academic crises. So, what causes these crises, and what can we do about them?

Where does academic stress come from?

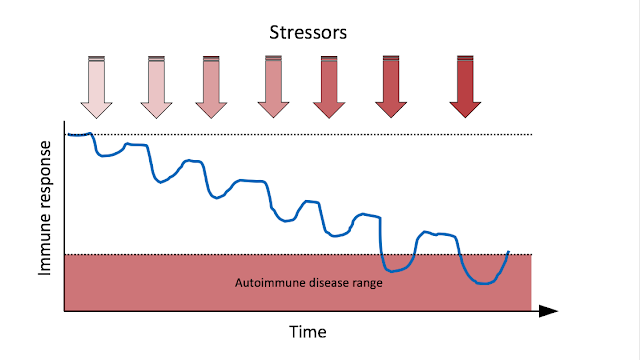

If you’re in the academic sphere I can only imagine that more than once you’ve asked (or continue to ask) yourself “why do I feel so stressed this week?”, “what is this stress going to do to me?”, “how can I stop being so stressed?”. At least I know I have. Eventually I caved and bought Prof. Robert M. Sapolsky’s book ‘Why zebras don’t get ulcers’, where he outlines the science behind why many of us have periods of sustained stress and anxiety, despite the absence of a lion waiting to pounce on us, and what this does to our body. Although the book is fantastic there are a number of statistics and diagrams that will also make you wonder whether those who designed the academic system, or facilitated its modern fiercely competitive atmosphere, have the exact aim of inducing misery and a multitude of long-term health problems on us all. Particularly striking was a figure demonstrating that repeated stressing gradually pushes our bodies’ immune systems towards failing. With each bout of stress the body responds with an ever increasing severity until we reach some kind of threshold, which, in the case of our immune system, is an autoimmune disease:

But all I could see as I looked at this figure was something like the figure below (apologies in advance to Prof. Sapolsky for butchering his nice figure), where instead of our bodies approaching immune failure repeated stresses and crises slowly drive us towards burnout in the absence of some kind of mitigation strategy:

After reading Sapolsky’s book it became clear that the academic system has a number of characteristics that just make it intrinsically stressful (again, not forgetting that many members of our community face additional stressors). Since any one of these aspects causes stress, it’s perhaps unsurprising that in concert, these stressors make many academics experience the occasional crisis - regardless of the passion/joy/love for the subject they study. Sapolsky’s “building blocks for psychological stressors”, and how I see these linked to academia include:

All is not lost - at least I don’t think it has to be. After all, many of you reading this have already successfully navigated many of these crises and continue to show resilience to these stressors. If you’re anything like me, then having some kind of strategy for when things get a little out of control is really helpful, and this is where biologist-turned-geographer Jared Diamond comes in, or rather Diamond’s crisis therapist friends. In Diamond’s 2019 book ‘Upheaval’ he aimed to evaluate the ways in which various countries have dealt with national crises, using a set of 12 criteria used by (albeit anonymous) crisis therapists that supposedly related to the outcomes of severe personal crises. Whilst reading about Finland’s war(s) with the Soviet Union, and the post-war rebuilding of Germany I got thinking about how I could apply Diamond’s crises outcome factors to develop my own personal crisis mitigation strategy for crises big or small - specifically, for those relating to stress resulting from work.

So here goes nothing, my attempt to convert Diamond’s list of 12 crisis outcome factors into an academic crisis mitigation plan, ready for the next crisis academia has to throw my (and now our) way:

1: Acknowledge that you are in a crisis

This step involves admitting to yourself that you’re actually experiencing some sort of crisis (if you’re unconvinced at this point then happy times - take a mini break to get a coffee, a snack, and some fresh air, and get back to it). Can you define the crisis you’re experiencing? Perhaps you feel like you are failing, as a result of a paper/job/grant rejection. Alternatively you might be having doubts that you are good enough to do your job or that academia is the right path for you. Acknowledging and accepting these feelings is an all-important first step.

2: Accept your personal responsibility to do something

The next challenge is to come to the conclusion that regardless of what is causing the crisis it is now your responsibility to change what you can to address and resolve it. Often external factors play a part in getting us to a crisis state - particularly in academia where stressful collaborators, uncooperative study organisms, or even worse, that arse reviewer 2, seem to be trying their best to make everything worse. Unfortunately, no matter how hard we try we can’t wrangle with each of these externalities and so it’s really down to us to take the initiative to address how we feel in response to them.

3: Delineate your specific problem(s) that need solving

Be specific about what exactly needs solving. Broadly thinking that it’s all gone to pot isn’t a manageable issue. Now’s the time to define what needs to change. This could be: needing a better strategy for approaching your thesis writing, having a meeting to discuss your experiments with collaborators/supervisors, coming up with a strategy for applying for grants/jobs, or even making the first step in thinking about new academic topics or even alternative careers to move into. There are many deeply entrenched issues in academia but compounding your stress of writing and submitting that important paper with general disdain and rage for the publishing industry is unlikely to help.

4: Get material and emotional help from others

Determine who in your immediate sphere, your friends and families or close colleagues can help you resolve the problems you just identified or support you through the resolution process. This could involve asking for advice about your different options e.g. chatting with close colleagues and friends about what experiments you could run to make up for failed ones, how to improve a grant or manuscript, or discussing career or personal changes or life uncertainty with friends and family. Now is also the time to consider whether your immediate colleagues/supervisors are providing the support you need to overcome your crisis. I don’t think supervisors have to (or maybe even should) necessarily be available for you to cry on their shoulder but empathy, and the ability to provide you with academic support is really important and part of their job. Unfortunately there will always be people who are let down by their supervisors in that regard, and I strongly urge the people impacted by these poor mentors to reach into the broader academic community where, from what I have experienced, there are plenty of kind supportive and smart people who would be honoured to help you get back on track.

One of the valuable aspects of academia is the level of connectedness between us all. Although this can sometimes add stress, like the perception of being in competition with all of our peers, it also provides us with the opportunity to observe how others handle obstacles and crises. We now have the possibility to see what respected (and even not so respected) peers do under different circumstances. How do they respond to strategizing about careers, or getting a paper through a difficult review process or navigating the tenure process - and what can I learn from them? Make the most of your academic network both formally and informally to get inspiration and advice on resolving your specific problems. If you’re stressed about career paths/options or your competitiveness for different grants or jobs this could involve looking through people's CVs online to see how people progressed, which grants they applied for or how much experience and output they had when applying for each. It could involve reaching out to academics you haven't met with yet who faced similar problems (e.g. with an analysis you’re stuck on to get expert advice on how to proceed).

5: Evaluate and reflect on your ego strength

This is one of the most difficult steps, especially, from my experience, for academics. This involves a firm rejection of the impostor syndrome voice in your head and requires you to establish and maintain your sense of self, your sense of purpose, and the acknowledgement of your value as an individual. This one is very personal, and seems to be variable based on personality type, upbringing, and culture, but I think being aware of the strength of your ego is an important aspect of overcoming obstacles. Without this strength of ego it is even harder to see your crisis as something that can and will be overcome and formulate a strategy to resolve it. Additionally, recognising and valuing your ego strength will stop you from spiralling and catastrophizing, something i’ve definitely been guilty of.

6: Carry out an honest self-appraisal

Some of you might be thinking “okay NOW it’s my time to shine” but again - honest self-appraisal does not equate to tearing yourself down, it’s about coming up with an objective view of yourself. This is hard and I suspect most people aren’t good at it, either inflating their sense of self worth or destroying it completely. I think the most constructive way of self-appraisal is to figure out which aspects of your personality or skill-set might be hindering the resolution of the specific issues you previously identified. One of the key ideas Diamond describes with relation to this is to retain and build upon our strengths and address our weaknesses in the constructive form of developing coping strategies. For example, if you are stressed about being uncompetitive for grants or jobs you can ask yourself whether this is objectively true, because you have assessed you have knowledge/skill gaps in some area, or skewed by self depreciation. If it really is true that you’re not competitive or aren’t good enough at something then you have at least identified areas that you need to work on and can now aim to acquire the specific skills needed to resolve your crisis. Conversely, if you conclude it is not true that you’re uncompetitive/inexperienced then perhaps working on reaffirming your skills to yourself is what you really need.

7: Draw on past experience of previous personal crises

Not only do your friends, family, and colleagues have tips to get you through your difficult patch, but so do you! The Poet Rumi once said “There is nothing outside of yourself, look within. Everything you want is there. You are That.” ...or something like that, and I don't know about you but he might have a point. After all, we all got this far and have undoubtedly already navigated a number of stressful situations and obstacles. Build on these experiences and use what you have learned. Also use your past experiences to normalise your feelings during future stressful periods. One example is understanding how you felt after your first manuscript or grant rejection and how, once you normalise these feelings the subsequent (and let's face it inevitable) future rejections won’t sting quite as badly.

8: Exhibit patience

Although tricky when in full crisis mode, try not to expect an immediate fix. There is likely no quick fix to your problem (and if there is... then go for that!) and after identifying the issue and searching for the solution the best option is to puzzle away at it rather than expecting to stumble upon a silver bullet. This is especially the case for revising manuscripts or grant proposals as well as job searching. Clinging on to the uncertainty or various possible outcomes outside of your control will only compound the stress. Do yourself a favour and stop refreshing the screen on that manuscript or grant decision page.

9: Strive for flexibility in your personality

Flexibility is key for overcoming specific issues as they arise and building long lasting resilience to crises in general. In my eyes, learning to deal with, and even appreciate unpredictability, is a real strength in academia. I am constantly faced with projects that would be much easier for me to undertake if I had more mental flexibility. This one is tough for me, and I imagine many others, who are real habit formers and/or suffer from compulsive behaviours. Reflecting on your past flexibility, and how it has helped you overcome novel problems is undoubtedly really valuable - there is likely more than one way to overcome each obstacle. I think working on this one could include: trying to step out of your comfort zone every once in a while, perhaps interacting with one of your colleagues you’ve never spoken to, signing up to give a talk at a symposium, or even signing up for a conference where you don't know any other attendees. Expanding your flexible comfort zone will really pay off in the long term.

10: Establish and asses your individual core values

What makes you, you? What are your core beliefs that you simply won’t budge on? Understanding your personal core values and how various crisis situations may conflict with these seems key to the resolution of loads of issues in academia. For example, your crisis may revolve around not being able to find a job in your department and constantly being told you need to move. This is well and good if you’re open to the idea of moving, but if your core value is that you want to stay where you are then that’s a direct conflict. It’s essential to confront whether this is non-negotiable, in which case you need to search for a solution elsewhere, or whether you might be able to compromise. Importantly I think this one links to part 2 where you need to take control of your own crises and so when strong conflicts arise between core beliefs and the crisis itself its important to understand whether you can find an approach that allows you to work around it rather than butt heads with it. Diamond points out that when the resolution to crisis conflicts with core values, crisis resolution is harder, but in contrast when solutions can be linked to existing beliefs our strength in these beliefs can help us reach a resolution. Here it’s also important to note that these core values are likely totally different for everyone. No one person’s core values are more real or valid than anyone else's, meaning you shouldn't expect everyone to understand or accommodate for your core values. Lots of problems in academia, like society in general, come from conflicts in core values - Do exams work? Should students have to do x, y, z before graduating? Is it moral or just to publish in this or that journal?. The best you can do is to be sure of your own values and how these relate to your own crises rather than concerning yourself with others (i’m looking at you twitter).

11: Assess your personal constraints

Undoubtedly those of us with fewer personal constraints have many things easier in academia. Sometimes these personal constraints could be considered core values but I think Diamond’s explanation is that these are essentially unchangeable and absolute whereas core values can be tweaked/changed or ranked. For example, it is not up for debate or discussion that you need to care for children/dependents. In the case of academia this obviously influences the crises you might face and the resolutions to these crises. I don’t have any experience with this but my interpretation of this criterion is to just make sure you are taking these rigid personal constraints into consideration when coming up with a solution. Additionally if you’re the friend/colleague for someone else in crisis try then to understand their personal constraints when offering advice just as you would try to acknowledge differences in core values. Whilst personal constraints often add complexity they can also be a source of structure and strength that can help in finding resolutions to different situations.

And there we have it, my simplified but structured approach for dealing with some of the stressors and crises that arise from academia. I’m going to try to put this structured strategy into action myself next time I have a bit of a wobble and make sure that instead of the harrowing trajectories above I can maintain some kind of buoyancy in my happiness (like the one below) whilst navigating this stressful job. Hopefully some of this can be helpful to you too, although if you think it's all nonsense then at least you can do the opposite. Be kind to yourself!

Academia is a difficult, competitive, career to make work. As a result, I think that both personal and professional crises or mini-crises are quite common (if you think this is a bit melodramatic then just replace the word crisis every time you read it with stressor). Perhaps I’ll write a post about whether I think the competition and resulting crises are unique to academia, or intrinsically a good or a bad thing another time, but I think this sentiment is pretty inarguable. I also think that pretending this isn’t the case, that pursuing an academic career isn’t difficult or doesn’t involve dealing with a sometimes flawed system, regardless of how much we wish it weren’t, is largely unhelpful and doesn’t help us address the different challenges we face both personally, and as a community. As a postdoc (and twitter user) I’ve become very aware of the breadth of common obstacles that everybody has to navigate from time to time in pursuit of an academic career. I’m also aware that in addition to these ‘common’ obstacles that impact everyone, there are additional obstacles that have a disproportionate, and frankly unfair, impact on specific fractions of our academic community in a manner of different ways. In this regard I count myself very privileged, having to predominantly navigate only what I deem as the most ‘common’ academic crises. So, what causes these crises, and what can we do about them?

Where does academic stress come from?

If you’re in the academic sphere I can only imagine that more than once you’ve asked (or continue to ask) yourself “why do I feel so stressed this week?”, “what is this stress going to do to me?”, “how can I stop being so stressed?”. At least I know I have. Eventually I caved and bought Prof. Robert M. Sapolsky’s book ‘Why zebras don’t get ulcers’, where he outlines the science behind why many of us have periods of sustained stress and anxiety, despite the absence of a lion waiting to pounce on us, and what this does to our body. Although the book is fantastic there are a number of statistics and diagrams that will also make you wonder whether those who designed the academic system, or facilitated its modern fiercely competitive atmosphere, have the exact aim of inducing misery and a multitude of long-term health problems on us all. Particularly striking was a figure demonstrating that repeated stressing gradually pushes our bodies’ immune systems towards failing. With each bout of stress the body responds with an ever increasing severity until we reach some kind of threshold, which, in the case of our immune system, is an autoimmune disease:

But all I could see as I looked at this figure was something like the figure below (apologies in advance to Prof. Sapolsky for butchering his nice figure), where instead of our bodies approaching immune failure repeated stresses and crises slowly drive us towards burnout in the absence of some kind of mitigation strategy:

After reading Sapolsky’s book it became clear that the academic system has a number of characteristics that just make it intrinsically stressful (again, not forgetting that many members of our community face additional stressors). Since any one of these aspects causes stress, it’s perhaps unsurprising that in concert, these stressors make many academics experience the occasional crisis - regardless of the passion/joy/love for the subject they study. Sapolsky’s “building blocks for psychological stressors”, and how I see these linked to academia include:

- A lack of outlets for frustration - exacerbated by fixed term contracts and little accountability from employers (if you’re wondering why academic twitter can be wild this is probably it)

- A lack of social support - perhaps from repeatedly moving lab/country and/or working such long hours that you don’t have time to build a local support network

- A lack of predictability - perhaps from not knowing how/where you’ll be employed in a year or two, or even day to day whether an experiment will work or your paper or grant will be accepted

- A lack of control - like applying for (and often getting rejected from) exceptionally competitive grants, or dealing with different corporate entities like universities or publishing companies where people outside of your sphere make career-impacting decisions

- A perception of things worsening - oh, I don’t know, maybe because your grant was cut with very little warning or colleagues were fired from a department en masse...

All is not lost - at least I don’t think it has to be. After all, many of you reading this have already successfully navigated many of these crises and continue to show resilience to these stressors. If you’re anything like me, then having some kind of strategy for when things get a little out of control is really helpful, and this is where biologist-turned-geographer Jared Diamond comes in, or rather Diamond’s crisis therapist friends. In Diamond’s 2019 book ‘Upheaval’ he aimed to evaluate the ways in which various countries have dealt with national crises, using a set of 12 criteria used by (albeit anonymous) crisis therapists that supposedly related to the outcomes of severe personal crises. Whilst reading about Finland’s war(s) with the Soviet Union, and the post-war rebuilding of Germany I got thinking about how I could apply Diamond’s crises outcome factors to develop my own personal crisis mitigation strategy for crises big or small - specifically, for those relating to stress resulting from work.

So here goes nothing, my attempt to convert Diamond’s list of 12 crisis outcome factors into an academic crisis mitigation plan, ready for the next crisis academia has to throw my (and now our) way:

1: Acknowledge that you are in a crisis

This step involves admitting to yourself that you’re actually experiencing some sort of crisis (if you’re unconvinced at this point then happy times - take a mini break to get a coffee, a snack, and some fresh air, and get back to it). Can you define the crisis you’re experiencing? Perhaps you feel like you are failing, as a result of a paper/job/grant rejection. Alternatively you might be having doubts that you are good enough to do your job or that academia is the right path for you. Acknowledging and accepting these feelings is an all-important first step.

2: Accept your personal responsibility to do something

The next challenge is to come to the conclusion that regardless of what is causing the crisis it is now your responsibility to change what you can to address and resolve it. Often external factors play a part in getting us to a crisis state - particularly in academia where stressful collaborators, uncooperative study organisms, or even worse, that arse reviewer 2, seem to be trying their best to make everything worse. Unfortunately, no matter how hard we try we can’t wrangle with each of these externalities and so it’s really down to us to take the initiative to address how we feel in response to them.

3: Delineate your specific problem(s) that need solving

Be specific about what exactly needs solving. Broadly thinking that it’s all gone to pot isn’t a manageable issue. Now’s the time to define what needs to change. This could be: needing a better strategy for approaching your thesis writing, having a meeting to discuss your experiments with collaborators/supervisors, coming up with a strategy for applying for grants/jobs, or even making the first step in thinking about new academic topics or even alternative careers to move into. There are many deeply entrenched issues in academia but compounding your stress of writing and submitting that important paper with general disdain and rage for the publishing industry is unlikely to help.

4: Get material and emotional help from others

Determine who in your immediate sphere, your friends and families or close colleagues can help you resolve the problems you just identified or support you through the resolution process. This could involve asking for advice about your different options e.g. chatting with close colleagues and friends about what experiments you could run to make up for failed ones, how to improve a grant or manuscript, or discussing career or personal changes or life uncertainty with friends and family. Now is also the time to consider whether your immediate colleagues/supervisors are providing the support you need to overcome your crisis. I don’t think supervisors have to (or maybe even should) necessarily be available for you to cry on their shoulder but empathy, and the ability to provide you with academic support is really important and part of their job. Unfortunately there will always be people who are let down by their supervisors in that regard, and I strongly urge the people impacted by these poor mentors to reach into the broader academic community where, from what I have experienced, there are plenty of kind supportive and smart people who would be honoured to help you get back on track.

One of the valuable aspects of academia is the level of connectedness between us all. Although this can sometimes add stress, like the perception of being in competition with all of our peers, it also provides us with the opportunity to observe how others handle obstacles and crises. We now have the possibility to see what respected (and even not so respected) peers do under different circumstances. How do they respond to strategizing about careers, or getting a paper through a difficult review process or navigating the tenure process - and what can I learn from them? Make the most of your academic network both formally and informally to get inspiration and advice on resolving your specific problems. If you’re stressed about career paths/options or your competitiveness for different grants or jobs this could involve looking through people's CVs online to see how people progressed, which grants they applied for or how much experience and output they had when applying for each. It could involve reaching out to academics you haven't met with yet who faced similar problems (e.g. with an analysis you’re stuck on to get expert advice on how to proceed).

5: Evaluate and reflect on your ego strength

This is one of the most difficult steps, especially, from my experience, for academics. This involves a firm rejection of the impostor syndrome voice in your head and requires you to establish and maintain your sense of self, your sense of purpose, and the acknowledgement of your value as an individual. This one is very personal, and seems to be variable based on personality type, upbringing, and culture, but I think being aware of the strength of your ego is an important aspect of overcoming obstacles. Without this strength of ego it is even harder to see your crisis as something that can and will be overcome and formulate a strategy to resolve it. Additionally, recognising and valuing your ego strength will stop you from spiralling and catastrophizing, something i’ve definitely been guilty of.

6: Carry out an honest self-appraisal

Some of you might be thinking “okay NOW it’s my time to shine” but again - honest self-appraisal does not equate to tearing yourself down, it’s about coming up with an objective view of yourself. This is hard and I suspect most people aren’t good at it, either inflating their sense of self worth or destroying it completely. I think the most constructive way of self-appraisal is to figure out which aspects of your personality or skill-set might be hindering the resolution of the specific issues you previously identified. One of the key ideas Diamond describes with relation to this is to retain and build upon our strengths and address our weaknesses in the constructive form of developing coping strategies. For example, if you are stressed about being uncompetitive for grants or jobs you can ask yourself whether this is objectively true, because you have assessed you have knowledge/skill gaps in some area, or skewed by self depreciation. If it really is true that you’re not competitive or aren’t good enough at something then you have at least identified areas that you need to work on and can now aim to acquire the specific skills needed to resolve your crisis. Conversely, if you conclude it is not true that you’re uncompetitive/inexperienced then perhaps working on reaffirming your skills to yourself is what you really need.

7: Draw on past experience of previous personal crises

Not only do your friends, family, and colleagues have tips to get you through your difficult patch, but so do you! The Poet Rumi once said “There is nothing outside of yourself, look within. Everything you want is there. You are That.” ...or something like that, and I don't know about you but he might have a point. After all, we all got this far and have undoubtedly already navigated a number of stressful situations and obstacles. Build on these experiences and use what you have learned. Also use your past experiences to normalise your feelings during future stressful periods. One example is understanding how you felt after your first manuscript or grant rejection and how, once you normalise these feelings the subsequent (and let's face it inevitable) future rejections won’t sting quite as badly.

8: Exhibit patience

Although tricky when in full crisis mode, try not to expect an immediate fix. There is likely no quick fix to your problem (and if there is... then go for that!) and after identifying the issue and searching for the solution the best option is to puzzle away at it rather than expecting to stumble upon a silver bullet. This is especially the case for revising manuscripts or grant proposals as well as job searching. Clinging on to the uncertainty or various possible outcomes outside of your control will only compound the stress. Do yourself a favour and stop refreshing the screen on that manuscript or grant decision page.

9: Strive for flexibility in your personality

Flexibility is key for overcoming specific issues as they arise and building long lasting resilience to crises in general. In my eyes, learning to deal with, and even appreciate unpredictability, is a real strength in academia. I am constantly faced with projects that would be much easier for me to undertake if I had more mental flexibility. This one is tough for me, and I imagine many others, who are real habit formers and/or suffer from compulsive behaviours. Reflecting on your past flexibility, and how it has helped you overcome novel problems is undoubtedly really valuable - there is likely more than one way to overcome each obstacle. I think working on this one could include: trying to step out of your comfort zone every once in a while, perhaps interacting with one of your colleagues you’ve never spoken to, signing up to give a talk at a symposium, or even signing up for a conference where you don't know any other attendees. Expanding your flexible comfort zone will really pay off in the long term.

10: Establish and asses your individual core values

What makes you, you? What are your core beliefs that you simply won’t budge on? Understanding your personal core values and how various crisis situations may conflict with these seems key to the resolution of loads of issues in academia. For example, your crisis may revolve around not being able to find a job in your department and constantly being told you need to move. This is well and good if you’re open to the idea of moving, but if your core value is that you want to stay where you are then that’s a direct conflict. It’s essential to confront whether this is non-negotiable, in which case you need to search for a solution elsewhere, or whether you might be able to compromise. Importantly I think this one links to part 2 where you need to take control of your own crises and so when strong conflicts arise between core beliefs and the crisis itself its important to understand whether you can find an approach that allows you to work around it rather than butt heads with it. Diamond points out that when the resolution to crisis conflicts with core values, crisis resolution is harder, but in contrast when solutions can be linked to existing beliefs our strength in these beliefs can help us reach a resolution. Here it’s also important to note that these core values are likely totally different for everyone. No one person’s core values are more real or valid than anyone else's, meaning you shouldn't expect everyone to understand or accommodate for your core values. Lots of problems in academia, like society in general, come from conflicts in core values - Do exams work? Should students have to do x, y, z before graduating? Is it moral or just to publish in this or that journal?. The best you can do is to be sure of your own values and how these relate to your own crises rather than concerning yourself with others (i’m looking at you twitter).

11: Assess your personal constraints

Undoubtedly those of us with fewer personal constraints have many things easier in academia. Sometimes these personal constraints could be considered core values but I think Diamond’s explanation is that these are essentially unchangeable and absolute whereas core values can be tweaked/changed or ranked. For example, it is not up for debate or discussion that you need to care for children/dependents. In the case of academia this obviously influences the crises you might face and the resolutions to these crises. I don’t have any experience with this but my interpretation of this criterion is to just make sure you are taking these rigid personal constraints into consideration when coming up with a solution. Additionally if you’re the friend/colleague for someone else in crisis try then to understand their personal constraints when offering advice just as you would try to acknowledge differences in core values. Whilst personal constraints often add complexity they can also be a source of structure and strength that can help in finding resolutions to different situations.

And there we have it, my simplified but structured approach for dealing with some of the stressors and crises that arise from academia. I’m going to try to put this structured strategy into action myself next time I have a bit of a wobble and make sure that instead of the harrowing trajectories above I can maintain some kind of buoyancy in my happiness (like the one below) whilst navigating this stressful job. Hopefully some of this can be helpful to you too, although if you think it's all nonsense then at least you can do the opposite. Be kind to yourself!

Comments

Post a Comment